Out with Land Acknowledgements and In with Land Connection

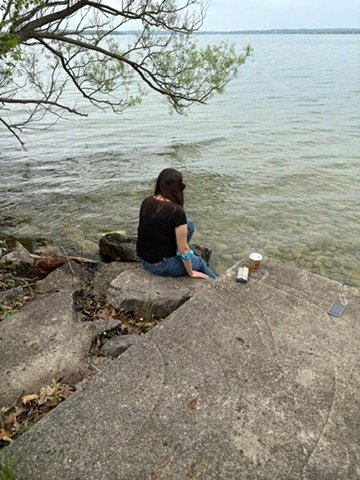

Over the course of the May-long weekend the Land Acknowledgement Team gathered on Rama First Nation in Ontario, navigating what it means to truly acknowledge the land and have a relationship with it. The Team, which consists of Sharla Mskokii Peltier, Trudy Cardinal, Charis Auger, Lyndsey Chamberlain, and select staff of the John Humphrey Centre, collaborated in building the framework of an on-the-land gathering for educators to be held in July in amiskwacîwâskahikan. This collaboration involved conversation, reflection, and intentional access to the natural landscape of Rama and surrounding areas.

Having the opportunity to meet with members of the community, including Aunty Vicky, a beading artist who is also a 60s Scoop Survivor, allowed us to realize the humanity of those children and families torn asunder and labelled simply as “the 60s Scoop”. Near the powwow grounds, which also hosts the Guinness World Records’ largest dream catcher, is a commemorative garden and memorial that honours the names of those children in the community who were taken away from their families.

The scars of residential institutions are made notice of in this memorial garden too, with the unmarked graves of innocents now protected with small, birdhouse-esque, homes meant to allow the spirits of those lost to enter and leave the space safely. Returning to the land went beyond the literal and physical, becoming emblematic of the potential that exists for learning, for healing, and for connecting with the community. Through guided walks around Rama and Muskoka Discovery Centre, we had the opportunity to meet Sharla’s brother Mark, an Elder and Knowledge Keeper, who shared how the peoples of Rama have lived with the land and the significance of fish weirs to that history. Their importance continued throughout our time together, through art highlighting how the weirs are in their own a way a tool of gathering life together, through the historical significance and access of the original weirs used in the community, to the Mnjikaning Fish Weirs National Historic Site, hidden away under busy roadways. It was journeys like this over the course of those three and a half days that allowed us to acknowledge the land as an everlasting presence that holds significance, not as something to take advantage of, but to respect, to be grateful for, to see as extensions of ourselves and of each other.

We left our gathering in May, with actionable goals and hopes to bring together educators, to bring about conversation, reflection, and collaboration towards a focus of land-based learning and indigenous context to education. This has culminated into a gathering to be held in July with said educators, working together on breaking apart that check-box mentality of simply stating a land acknowledgement, and growing instead into societal conversations about acknowledging the land, starting with the first of the next seven generations, in our schools.